Fight Club: A Novel

Chuck Palahniuk

1996

An

Alexandrine Couplet Comparing The Book To The Movie

Certain parts make more sense and the scope

is bigger,

but you all saw the film—it’s pretty

much the same.

|

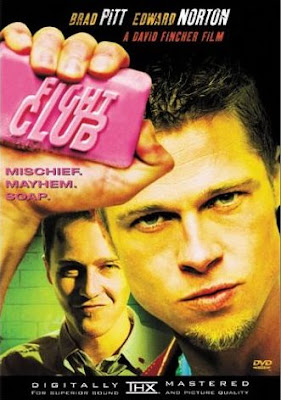

| The movie’s so good you’d never guess I was Brad Pitt’s body double in this scene. |

I’m about to make a bold statement:

Chuck Palahniuk is one of the best writers of the 20th century. I’ll

qualify that by saying half his books aren’t all great. I actually finished Choke

(yeah, I’m the one) so I know they’re not all diamonds. But when he’s on, like

in Survivor,

Rant,

and yes, Fight Club, it’s transcendent. It’s the sort of writing that

makes writers jealous.

Enough ass-kissing.

Fight Club,

though it didn’t really get credit for this, largely defines its generation,

and the current one. It’s about how we’re so busy being told what to do and own

and how to define ourselves, and trying to live up to the unrealistic, preset expectations

of our parents and society, that we can’t figure out how to do what we want or make

ourselves happy. It’s about how consumer culture and advertising has perverted

us, and when this was written that wasn’t the common notion it is now. Of course,

because Chuck wrote it, Fight Club decides the only solution to this problem

is the Nihilistic destruction of society, worldwide.

|

| It would have been much easier for Tyler to hire this guy. Just sayin’. |

The Nihilist theme is one of the few

differences between the book and movie. In Fight Club The Movie, you

don’t see or understand the full scope of Fight Club/Project Mayhem/Tyler

Durden’s Wet Dream. In the movie, Tyler and Friends are anarchists trying to

take down society. They’re blowing up financial buildings. (I can’t be the only

one who notices that terrorists blowing up financial buildings was totally

acceptable in 1997, but that’s a whole different discussion). In Fight Club

The Novel, they’re dropping a financial building on top a natural history museum

– attacking corporate America as well as history and culture. That’s an attack

with a very different purpose. It’s also a worldwide movement in the book.

The other big difference, really, is

that you understand a lot better in Fight Club The Novel how it’s all

really about Marla all along, that Tyler is doing all this, taking a sledge

hammer to society at large, because he’s so emasculated and callow that he doesn’t

have the balls to ask her on a date.

|

| Nothing says “diner and a movie” like the destruction of society. |

—Alternate Picture—

|

He could have just asked Snoop Dogg for

advice.

Really, it would have been a much easier

solution.

|

Oh yeah, and one more difference: Meatloaf is in the movie.

|

|

Because he loves Chuck Palahniuk,

and he’ll do anything for love.

|

Look, it’s an excellent book. It’s as

good a book as the movie is a movie, and they’re both classics. If you haven’t

read it, you should. Or just watch it if you haven’t in a few years. Both

couldn’t hurt.

|

| Because this image is just too iconic not to include. |